The Development Of Water Meadows On The Salisbury Avon, 1665—1690 by Joseph Bettey

Abstract

The development and rapid spread of water meadows through the chalkland valleys of Wessex was a major agricultural innovation of the seventeenth

century. This article traces the history of a large-scale project for watering the meadows along the wide valley of the Avon south of Salisbury.

The successful completion of this scheme, in spite of the difficulties encountered and the expense involved, is a tribute both to the tenacity

of the manorial steward and to the value of the early grass and reliable crops of hay which watered meadows provided.

The advantages of watering meadows to produce early grass for the sheep flocks and abundant crops of hay were already well known in Dorset and

south Wiltshire by the early decades of the seventeenth century. Successful schemes were implemented in the century along the Frome and Piddle in

Dorset and along the Wylye, Nadder, the upper Avon and the Kennet in Wiltshire. This article adds to the existing literature by describing a

remarkable project for creating some 250 acres of water meadows along a four-mile stretch of the river Avon at Downton, south of Salisbury, which

was started in 1665 and finished by 1690.

This ambitious scheme was financed by the landowner, Sir Joseph Ashe, but was planned and executed by his steward, John Snow. Ashe (1618-86) was

a member of a leading family of west-country clothiers. He had been educated in London and became a wealthy London merchant, dealing in cloth;

he was a member of the Drapers’ Company and of the East India Company. He lived at Twickenham (Middlesex) and was created a baronet by Charles

II in 1660. From 1662 to 1681 he sat as one of the two MPs for the borough of Downton in Wiltshire. In 1651 he acquired the large farm of New

Court in Downton and in 1662 obtained a lease of the whole of the manor of Downton from the bishopric of Winchester. Thus Ashe secured control of most

of the Avon valley from Alderbury to the Hampshire border south of Downton, including large farms at Witherington, Charlton, Standlynch and New Court,

together with Loosehanger Park on the higher ground south-east of Downton. Ashe died in 1686, and the estate was left in the hands of his widow,

Lady Mary Ashe, until his son, Sir James Ashe, succeeded in 1698. He retained the Downton estate until his death in 1714. Since the Ashe family

never resided at Downton, all aspects of estate management were entrusted to the steward, John Snow. After John Snow’s death in 1698, his son,

Leonard, followed him as steward for Six James Ashe.

John Snow came from Winterbourne Stoke in Wiltshire, where he owned a house, paying tax for three hearths during the period 1676-89. He was described

as ‘yeoman’ and was married with several children. In 1662 he was engaged by Sir Joseph Ashe to manage the newly-acquired estate at Downton, end moved

with his wife and family into the Lodge at Looschanger Park. In 1665 he was formally appointed as steward of the manor of Downton’ The Lodge was

apparently not ready for immediate occupation and in a letter to Snow of 16 April 1665 Sir Joseph Ashe wrote ‘I long to heare that you are at the

Lodge setled’. Snow’s account book shows considerable work and expenditure on the house and garden at Loosehanger during 1664-5. John Snow was evidently

a man of ability and determination. In addition to managing the estate, Snow undertook numerous other tasks, personal and political, for the Ashe

family. He fostered good relations with the hundred and more electors of Downton, managed elections and entertained the voters. He carried the

rental income to Twickenham, and supplied food-stuffs and livestock to the household there. Servants were engaged from Downton to work at Twickenham,

and he even gave advice about a possible bridegroom for Lady Mary’s god-daughter. When Sir Joseph Ashe established a free school at Downton in c. 1676,

John Snow was involved in making the detailed arrangements. He made several visits to Sir Joseph's properties in Yorkshire to advise on estate

management, drainage schemes, tenancies and farming matters. Snow was evidently trusted and highly regarded by his employer, although this did not

prevent Sir Joseph from grumbling ceaselessly about the expenditure at Downton. It was due to Snow’s enthusiasm, powers of negotiation and perseverance

that the water-meadow project was successfully completed.

For the Ashe family the purchase of New Court and the lease of Downton was highly profitable. An account of 1682 shows a rental income from New

Court of £460 a year, and an income from the other Downton properties of £750. The annual rent paid to the bishop of Winchester was £150. In addition

the lease gave Ashe control of one of the two patiamentaiy seats for the borough of Downton.

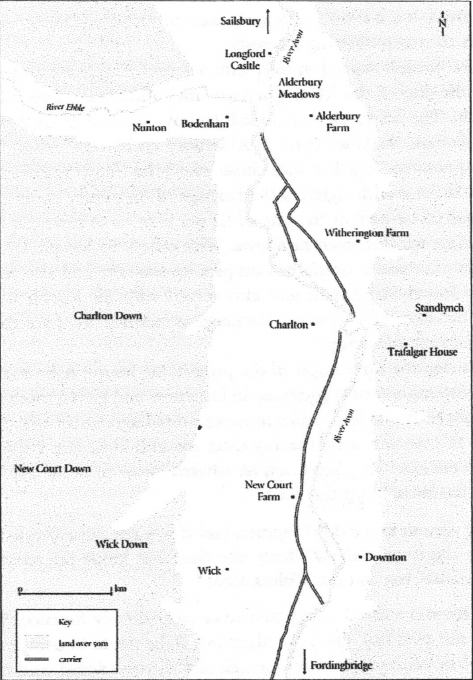

The Downton project (Figure 1) was on a much more expansive scale than any of the eatlicr projects to create water meadows. It involved the excavation

of two new channels for the water, one starting from Alderbury, the other from Chariton; each was 24 feet wide. Weirs and hatches were built in order

to divert part of the strong, fastflowing river Avon along these ‘Main Carriages’. From them numerous subsidiary channels took water to the various

meadows. The scheme involved careful surveying, major excavations, substantial hatches on the Avon built strong enough to withstand the current and

to survive winter floods, and numerous smaller hatches on the feeder channels. The surface of each meadow had to be carefully prepared with ridges and

drains, so that the surface could be covered with a thin sheet of moving water coming ‘on at a trot and off at a gallop’? Many new bridges were needed

and those on the river itself had to allow for the passages of barges on the proposed canal which, it was hoped, would give access from Salisbury to the

coast at Christchurch. Bridges had also to be provided for the footpaths which linked farms and settlements on either side of the valley. Compensation

had to be paid to neighbouring landowners, tenants and commoners through whose land the new channels passed or whose grazing rights were affected.

Agreements had also to be made with millers and with those owning fishing rights. It was John Snow who undertook all these negotiations and who

organized the large-scale works involved. It is a tribute to Snow’s skill and patience that agreements were successfully concluded with so many differing

interests.

The project started in 1665 with a serics of agreements with neighbouring landowners over the digging of the Main Carriage from Alderbury. Eventually

more than 40 contracts were made. The landowners included Thomas Jervoise of Britford, Lord Coleraine of Nunton and Bodenham, Sir Giles Eyres of

Alderbury and several others. Numerous copyholders had to be compensated, together with those who John Snow desctibed as ‘the Earbidgers of Alderbury’,

that is those with rights to the herbage of Alderbury common meads. Each of the commoners agreed to be paid at the rate of £4 per acre or to have the

right to take water from the Main Carriage for their own meadows. With others Sir Joseph Ashe agreed to lease the land required or to purchase it outright.

Complex agreements had also to be made with Maurice Bockland who leased Standlynch and also served with Sir Joseph Ashe as member of parliament for the

borough of Downton. Bockland undertook to share the cost of bringing water into the Standlynch meadows.

During the early stages of the project, Sir Joseph Ashe took a close and enthusiastic interest, making numerous suggestions in his letters and giving

careful instructions over details. As early as 1665 he urged John Snow to make a rapid agreement with the commoners at Chariton, telling him to ‘sweeten

it by making their grounds rich, and I wil oblige them one way or other to their enrichment’. Above all, he advised Snow to avoid any breach with the

commoners since this would hold up the work;

"be sure to keepe off a rupture, and if you see cause invyte the persons there to a dynner and be merry with them. Delay noe tyme but keepe the scent hott.

Goe on as fast as you can, that we may put our afaires afoot."

By 1671 some of the water meadows were already functioning and were producing early grass and plentiful hay. On 5 February i671 Ashe wrote to compliment

John Snow on the improvement to Witherington farm meads at Katherine Mead, and on the surplus hay which could be sold. “This hard weather I hope wil bring

you customers for our fodder, which now begins to be understood with you well enough’

In 1675 a second Main Carriage was begun in order to water the meadows beyond New Court. As the scheme progressed, however, problems arose and Ashe

became more and more concerned about the rising costs. John Snow had originally estimated that the enterprise would cost £2,000, but in 1672 he wrote

2 memorandum explaining why ‘the works come to near duble the expenses at first proposed’. He explained that more hatches and more trunks on hatches and

stops proved very chargable by reason the ground was so boggy where they was put in and all the meads so soft’. Because of the soft ground horses could

not be used to shift soil, bring gravel to assist drainage or cary clay to strengthen the banks of the main carriage and fill boggy places. Moreover,

‘the fetching gravill so far and the materialls was very expensive and likewise the making the west maine carriage and the west maine draine’. Snow’s

explanation of the rising costs illustrates the difficulties he faced with such a large, untried project, and the problem of accurate surveying to

ensure an even flow of water and adequate drainage.

The project created other unforeseen problems. The major excavations caused alarm over damage to the river banks and the possibility of flooding

which was a constant danger for the low-lying settlements along the valley. In 1673 John Snow was summoned before the Assizes at Salisbury to answer

charges of ‘throwinge in of stones and rubbish into the river of Avon in the liberty of Charleton within the said parish of Downton’. He was acquitted

after obtaining the signatures of nine local residents certifying that ‘the earth and gravell throwne in on the south side of the said river’ were to

strengthen the banks and prevent their erosion.” A year later Sir Joseph Ashe was accused before the justices at Quarter Sessions that he had interfered

with the water course at Downton and caused flooding. Again John Snow persuaded 22 local inhabitants to certify that the work had not damaged the water

course or highways and was ‘not at all prejudiciall or any publique nuisance’.

There were also problems over mills and interference with mill leats. Agreements had to be made over the use of water for the corn mill at Bodenham

and the large corn and fulling mill at Downton. Most affected was the corn mill at Standlynch. This had been rebuilt with a new weir and leat in 1575.

The effect of the new water courses created many problems over water supply and meant that the mill had to be rebuilt on a new site in 1697. This mill

survives, complete with its ‘eel house’ where large numbers of eels were caught each year during their migration, providing a useful secondary income

for the miller. The newly-built ‘mill and eele fishery’ was let for 21 years for £44 per annum.

Faced by continuing criticism from his employer over the rising costs, John Snow responded by making a remarkable offer. On 25 November 1674 he signed

an agreement in which he acknowledged that since 1665 Sir Joseph had

"by my hands and by my advise layd out great somes of money importinge above Two Thousand pounds upon drowning his meadowes in the parish of Downton

that belonged to Newe Court, Wythington and those meadowes in the possession of John Brewer, which hitherto have not rendered him any proffitt. And

whereas I have suggested to the said Sir Joseph Ashe that the aforesaid meadowes contayning in all about 200 acres have had their improvement suitable

to the moneys desbursed ...’. He went on to give three examples of the increased value of the meadows:

Brewers Farm 74 acres of meadow previously worth £74 per annum now worth £148 per annum

Witherington Farm 50 acres of meadow previously worth £20 per annum now worth £100 per annum

New Court Farm 7o acres of meadow previously worth £80 per annum now worth £180 per annum.

If the above meadows could not be let to tenants at these improved rents, John Snow undertook by this agreement to rent them himself; ‘I, John Snow,

wilbe tenant [for the meadows] myself for the terme of fower yeares and after the terme encrease the rent as the same t=! deserve’.

John Snow’s confidence was justified and the meadows were rented to tenants at the improved rents. This formal agreement, signed by both parties,

shows that John Snow was deeply affected by the complaints of his employer, and that he felt personally responsible for recommending such a costly project.

It also reveals that by 1574, only nine years after the proicct had started, almost 200 acres of meadow were being watered, and the watering had already

reached New Court, a short distance north of Downton. John Snow’s bold response did not stop the criticisms, however, and Six Joseph continued to grumble

about the expense. Among the Ashe papers relating to Downton are swe copies of a long document dated 1676, setting out the advantages and profits of water

meadow: and rebutting possible objections. There is no indication of the author, but it seams likely that it was produced by John Snow in response to

continuing censure. Since much work remained to be done in extending the system of water meadows, it may be that this document was also intended to obtain

the co-operation of other landowners. Having already negotiated many agreements, John Snow seems the most likely author of a paper which proclaims that

amicable accord could be achieved over all objactions. It is certainly a remarkable testimony to the value of water meadows. Entitled “Argument to shew

what greate profitt may redound to the owners of land upon a free ymprovement, by drowninge, wateringe or drayninge’, the first part is in the form of a

petition in which the advantages of creating water meadows are listed as follows:

Imprimis, by soe doeinge there will be a greater increase in hay.

Item, there will be greate increase of cattle.

Item, thereby will be a greater increase of corne.

Firste, That there wilbe a greater increase of hay by wateringe of meadows & Knowne by common experience. Hay beinge plenty men may keepe the more

cattle whereby their ground may be much bettered and ymproved. Theyre ground being thus bettered and ymproved there wilbe a greater increase of corne

and the after grasse of their grounds thus ymproved wilbe of greate benefitt for the feedinge of cattle both to fatt and also for butter and cheese.

Theis thinges considered, wee desire that there may be a free ymprovement by drowninge or drayninge of meadowes in all such places where it may be done

without prejudice to other men.

It is notable that whereas in most places throughout the chalkland region of Wessex, the early grass produced by the water meadows was used to feed sheep,

enabling larger flocks to be kept and more arable land folded, the emphasis in this document is on hay, cattle. butter and cheese. This reflects the

particular circumstances at Downton where the proximity of Salisbury and easy access to Winchester, Southampton and Portsmouth made dairy farming and

livestock production proitable. Large sheep flocks were also kept on the Downton farms and were folded on the arable land as was customary throughout

the chalklands, but there was also an emphasis on milk and beef production which became increasingly profitable during the later seventeenth century.

In addition, because the Avon valley south of Salisbury is much wider than most other chalkland valleys, sheep flocks had to be driven longer distances

than usual to feed on the water meadows, return to the downs and then be driven back to be folded at night on the arable land. Moreover, it was relatively

easy to cart dung to the arable fields from the farmsteads. The sheep fold remained important, but was not such a crucial feature of corn production at

Downton as it was elsewhere.

The rest of the ‘petition’ is concerned to refute possible objections to the creation of water meadows. The first objection was ‘But what yf there be

any mill either above or belowe that may be hindered by it?”. The answer was that equitable agreements could be made for the use of the water and

‘wateringe of the ground doth not soe much hinder the miller, but that he may grinde to serve his occasion’. Another possible objection was over flooding

or possible damage to the highways. The answer was that ‘those that have share in the drowninge shall equally pay theyre parte towards the repayringe of

the way soe farre as the way shalbe prejudiced by them’. Other objections concerned possible damage suffered by other landowners through digging of

channels and drains, building weirs in the river and setting up hatches to divert the water. Again, these objections were brushed aside by answers such

as ‘lett the owner of that ground have satisfaction according to his damage’; or ‘let satisfaction be given accordinge to the worth of that ground that

shalbe diged up or covered with bancks for the bringinge in of the water’. Further it was argued that agreements could be made whereby several men could

take turns to use the water, ‘lett the water be ymployed upon each man’s ground by course soe many dayes one as the other accordinge to theyre proportion

of ground’.

Finally, the author requested that

"And as for those grounds which some do mowe and others doe feede, yf the major parte doe agree that it may be drowned, wee desire that it may be done,

and soe likewise for the inclosinge of commons for drowninge. And lastly that all covenants and agreements be drawne and kepte in the court rolls or

parish registers."

Even this eloquent defence of watering meadows did not stop the complaints of Sir Joseph Ashe over the expense and problems of negotiating with other

landowners. On 22 March 1677 he wrote to John Snow ‘I thinke this cursed wateringe hath given me 10 tymes the trouble that all the other concernes of my

life hath done’. The heavy costs continued however, especially wits because of the need to install so many hatches to control the flow of water. On 15

April 1678 Sir Joseph wrote to Snow ‘When you will consider the perpetual troubles and constant laying out of money and none coming in you need not

wonder I am sicke of those designes’.

It was not to be expected that such a major scheme could be accomplished without local objections and complaints about John Snow. A diary of proceedings

at Downton manorial court 1681-94, kept by a prominent copyhold tenant, George Legg, is full of criticisms of Snow and his disregard for manorial custom.

In April 1682 Legg complained that Snow ‘will allwaies be fidling in something for his private gaine and incroaching to break our customs as much as it

lieth in him to doe ... He cares not the wrong he does in this kind’. In 1694 a group of Downton residents wrote to Lady Mary Ashe to complain about

Snow’s actions, exhorting ber “not to hearken to the advises of Mr Snow, who is little moved with cryes of the poore where a little small interest is

concerned’.

The few surviving accounts showing the detailed costs of construction are all from the last decade of the project. They reveal regular payments of 12d.

to 18d. per day to labourers digging channels and drains and excavating foundations for bridges and hatches. Stone was brought from quarries at Chilmark

and Fovant; chalk and gravel came from the surrounding downland; masons were paid 2s. 6d. a day for building bridges and the sub-structure or ‘landfasts’

for hatches. Bricks and lime came from local kilns, including numerous deliveries of bricks from Joseph Stokes at Brickmill in Downton. Timber was brought

from nearby woodland, much of it from Hale, south of Downton, and some from Loosehanger Park. Carpenters were employed at 2s. per day to build a variety

of hatches which could be raised or lowered to divert the flow of water as required. These included ‘hands’ or large hatches with as many as ten ‘eyes’

or apertures in the main streams, two or three ‘eye’ hatches in the subsidiary channels, ‘trunks’ or drainage channels, and ‘bunnels’ or culverts to

supply water to some of the carriers and minor water courses. The Downton blacksmith, Valentine Edsell, made the ironwork and provided the nails for the

hatches and their equipment. John Snow paid himself 3s. 4d. a day for surveying, ‘setting out foundations’ and directing the work, since presumably he

regarded this as additional to his regular work as steward.

Whilst these remaining accounts provide much information about individual costs, it is impossible to compute Ashe’s investment over the quarter century

it took to complete the project. When John Snow admitted in 1674 that more than £2000 had already been spent, the work was to continue for a further

16 years and included the construction of a second main carriage. By 1690 when more than 250 acres of water meadows had been created along the valley,

the total cost to the Ashe estate cannot have been far shoxt of £5000. This is in ine with the figure of £20 per acre for the construction of water

meadows given by Thomas Davis in the General View of the agriculture of Wiltshire (1794) although he, no doubi, was thinking of much less ambitious schemes.

In spite of Sir Joseph’s complaints about costs, the Downton water meadows were evidently a technical success and smaller schemes were soon started by

neighbouring andowners. At Nunton and Bodenham near the junction of the Ebble with the Avon, Henry Hare, Lord Coleraine, the owner of Longford Castle,

made an agreement in 1676 wiih two other endowners, Edward Froud and Elizabeth Clarke, for the creation of water meadows. The agreement included the

digging of ‘a great trench or main carriage’, the right to divert water fom above Lord Coleraine’s paper mill at Nunton, a rental of £3 per annum to

be paid for the water, the obligation to maintain the channels and hatches, and the respective turns or ‘stems’ for use of the water. Each party was

to have the water for 14 days and nights ‘and then the stem or turne for the other party ymmediately to begin or succeed’. The same agreement also contains

references to meadows on the Ebble at Odstock called King’s Mill Mead and the Marsh which were being watered by the tenants of Sir John Webb. Elaborate

arrangements were included to ensure that each tenant had a fair share of the water. During the 1680s a weir was built across the Avon at Britford by

Thomas Jervoise for watering the meadows there. A few years later water meadows were created beside the river Nadder, on the earl of Pembroke’s manors of

Burcombe and Ugford, and a waterman or ‘drowner’ was appointed to ‘look after the Floating of our Meades with water and drawing the said water off againe

as he shall think most proper’.

By 1690 the ambitious scheme for watering the Downton meadows had been completed, and a long list of all the channels, trunks, weirs, hatches and bridges

was compiled together with a note of those responsible for their maintenance. In spite of all the problems and controversy it had created, the project

had been remarkably successful. As well as the meadows created by the commoners at Alderbury and Charlton, and the meadows along the Ebble, the excavation

of the main carriages and the diversion of the water from the river Avon had transformed farming in the manor of Downton. During the 25 year period, some

40 acres of water meadow had been created at Witherington; at Standlynch there were nearly 100 acres of watered meadow; there were 76 acres of water meadow

at New Court Farm, and a similar acreage at Wick and along the Avon south of Downton as far as the Landshire Ditch which marked the county boundary.

The value of the meadows was doubled as a result of the watering. In 1628 and again during the 1650s the meadows at Witherington, Standlynch and New

Court were valued at £1 per acre. By 1682 the unwatered meadows remained at £1, but the watered meadows were said to be worth £2 an acre. The improved

values were not confined to the meadows. The early grass and reliable crops of hay provided by the water meadows meant that more livestock could be kept

and increased crops of wheat and barley could be grown, increasing the value of the whole farm. A valuation made of part of Sir Joseph Ashe’s estate at

the time of his death in 1686 lists both the ‘natural’ and the ‘improved’ values. The larger part of New Court was said to be worth £420 per annum

‘naturally’, but £520 ‘with the improvement’. The rest of New Court was worth, £64 15s. od. per annum ‘naturally’ and £148 ‘with the Improvement’.

Witherington Farm was ‘naturally’ worth £122 10s. od. per annum, but £184 7s. od. per annum ‘with the improvement’. Standlynch was let to the Bockland

family on a long lease, and was not included in the valuation of 1686. In 1700 the 734 acres of ‘arable, meadow well-watered, and pasture’ (including the

downland grazing) was producing a rent of £400 per annum or 10s. od. per acre; this was the same rate as the improved rental of New Court where 1,136 acres

were let for £668 per annum.

The effect on the landscape of the valley can still be seen in the surviving meadows and water channels. Figure 1 shows the extent of the whole scheme

and the work involved in excavating the main carriages. The full scale of the project is only evident when seen on the ground. The long straight main

carriages are still full of fast-flowing water and contrast with the sinuous natural course of the river. The subsidiary channels, drains, weirs and

culverts survive, and the ridged surface of the meadows is still clearly visible. The foundations for the hatches and culverts are well-built in stone

and brick, but the disused meadows now present a sad picture of neglect and decay. In a few places the late eighteenth-century ironwork mechanism for

operating the hatches survives, and is stamped ‘B. DUTCH. WAR’. This has given rise to the widespread but erroneous local belief that the water meadows

were conceived and laid out by Dutch immigrants. In fact, the ironwork was supplied by the foundry of Benjamin Dutch of Warminster.

The early grass and plentiful hay provided by the meadows, and the consequent ability to keep more livestock, had a further profound effect upon farming.

This was immediately obvious at Wick where nearly 300 acres of downland had already been converted to arable by 1700. A similar extension of arable on the

eastern side of the valley was made at Witherington, and by the early eighteenth century Witherington Farm included 328 acres of arable. At New Court

Farm the farmhouse and a large aisled barn of nine bays were rebuilt by Sir Joseph Ashe in c.1680. At that time there were 346 acres of arable; by 1716

a further 90 acres of arable had been added by the cultivation of downland and former pasture. At Standlynch Farm there was another development. John

Snow’s arguments of 1676 in favour of water meadows had included the fact that the meadows ‘wilbe of create benatin: for the feedinge of cattle, both

to fatt and alsoe for butter and cheese”. His faith was confirmed by the establishment of Standlynch Dairy Farm during the late seventeenth century, using

the early grass and fodder provided by the water meadows to sustain milk production throughout the year.

The vision and persistence of John Snow and the grudging expenditure of large sums of money by his wealthy employer, Sir Joseph Ashe. had transformed

the farming and landscape along four miles of the Avon valley and had provided an example which was being emulated on neighbouring manors. By the eighteenth

century water meatows had become an essential feature of the sheep/corn husbandry of the chalklands and empert observers could describe the value of

the early grass produced by the meadows as “aimost incalcuable' aod a vital element for successful arable farming on the thin chalk soils.

The Downton water meadows remained in use until the twentieth century when the cost of labour, the availab ility of artificial fertilisers and new fodder

crops lede gradually to their abandonment. Some meadows at Witherington were still beimg watered during the 1950s, but had been abandoned by 1960. Water

meadows at Britford on the Avon. north of Downton, are still in use and continue to be managed in the traditional manner.