The Development Of The Salisbury Avon Navigation - by Donald E Cross

Work was begun in 1675 when the Bishop of Salisbury cut the first turf of the new waterway. Locks and canalised ‘by-pass’ stretches were made, and in 1684 two 25 ton barges passed upriver to Harnham Bridge in Salisbury. The navigation was used for a short time, and in 1687 a Code of Regulation and Tolls was issued. Then severe floods washed away many of the works and debris plugged the dredged channels. The cost of repair and restoration was beyond the finances of the managers. In 1699 a Bill was presented to Parliament by those interested in getting payments of their claims for lands damaged by the navigation works. Some work was done which allowed navigation to be resumed after 1700, but by about 1730 the navigation was abandoned for good, and the prospect of Salisbury as an inland port disappeared for ever.

Recently attempts have been made to identify relics of the seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century works along the river, as one of the projects undertaken by the Salisbury & South Wiltshire Industrial Archaeology Society.

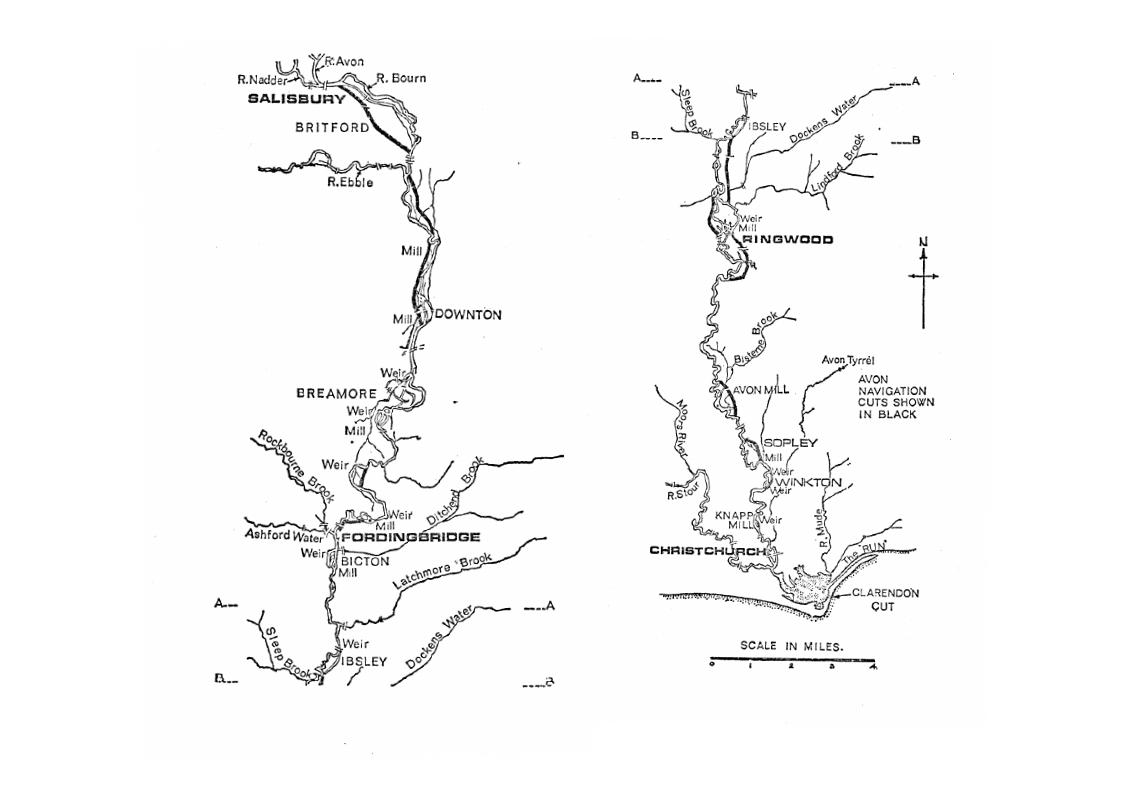

Probably, the first section cut was the existing stretch from the main river below Riverside Meadows and Churchill Gardens in Salisbury (NGR 41/148292) through Britford to rejoin the main stream at Longford Castle (NGR 172267). This section is clearly marked (as are other lengths of canalised river made for the navigation) on Naish’s Map of Salisbury (1751). Andrew and Drury’s map of Wiltshire (1773) also shows this length of navigation marked and named as ‘The New Canal’.

The Britford length is still clearly identifiable. The bridge at Britford Farm is triple-arched with the centre arch larger than the other two and giving at present about 3ft 6in clearance at normal waierievel. This bridge has a timber parapet balustrade. The bridge over the navigation cut between Dairy Farm and Manor Farm, Britford, is in similar style but with only a single brick arch. It is felt both these have been later reconstructions of the eighteenth century during the ‘water-meadow’ period.

On the north side of the last-named bridge (NGR 159278) is the only remaining and clearly-recognisable lock of the navigation (illustrated on p 153). If dredged, the lock depth would probably be 4-5ft, possibly more if the bed could be drained and the exact floor construction explored. The fall at the present sluices is not more than 2ft, and the whole lock and stretch of canal here is embanked about 5-6ft above the surrounding water-meadows. The iron sliding sluice-gates at the northern end of the lock are worked by hand-rachet gearing, with ironwork embossed ‘V. Armitage, Maker, Salisbury’ and are of mid-nineteenth-century date. The walling of the lock is doubtless of the period of the navigation’s operation, but certain alterations to service the eighteenth-century ‘water-mcadows’ system are obvious. This stretch of cut ends by rejoining the main river close to Longford Castle where a boathouse now covers the entrance (NGR 173267). There is no evidence of another lock, though there is some brick walling.

At Downton another navigation channel runs from above New Court Farm (NGR 175227) under the road in the borough west of the main river and rejoins the main stream about half-a-mile below after having been much affected by water-meadow works. On the north side of the present road bridge carrying the B 3080 through the borough, the stream is brick-walled with some ironstone-dogger edging similar to the Britford lock. The bridge is of brick and a similar style also to Britford. On the north-east side of the stream adjoining the cottage is a large ironstone ‘milestone’ tncorpocated in the walling on its side. This is inscribed with the numeral ‘3’, but its significance has not been determined and the number may be associated with the numbering of Downton borough prior to the 1832 Act for voting purposes.

It was further attempted to determine the route of the navigation cuts as shown on Naish’s map below Hale and past Wood Green and Breamore, but, although several channels can be traced through the meadows on the east side of the main stream, no conclusive proof could be found. There are several brick-built bridges carrying the Wood Green-Breamore road across the valley but most are more recent—one is dated 1908—and the extensive use of the flood-plain for water-meadows makes for further problems in establishing the line of the navigation cut.

At Fordingbridge, however, more encouraging evidence appears, especially at the Horseport—a significant name in itself (illustrated on p 153). The navigation is shown by Naish as leaving the main river below Burgate House, passing the town on the east side of the main river and rejoining below the bridge by the recreation ground. Though the original channel is untraceable in the meadows north of the Criddlestyle-Godshill road and at Burgate House, it gradually appears as a drainage ditch in the field nearest the Horseport and passes under the A 338 road by another brick-arched single-span bridge with stone parapets. The stream is bounded by brick walling on both sides for some 35yd to the north, but there is no evidence that this was lock walling. The original channel, and therefore the depth under the bridge, would have been much deeper, but is now much in-filled with silt and rubbish. The cut goes round the Victoria Rooms (a public hall) and the land on which this stands, together with the adjoining cottages, was very likely a wharf serving the navigation and later built on in the nineteenth century. The navigation rejoined the river at NGR 149142.

Boats on the Avon at Ibsley near Ringwood are depicted in a print in nearby Harbridge Church, but Naish’s line of a cut made almostdue south past Ellingham Church coincides with the existing line of a stream passing under the private road to Somerley Park just south of the church. (NGR 144082). The bridge carrying the road is fairly recent and of reinforced concrete with concrete bed on the stream. The parapet bricks, however, are older and appear to have been re-used, perhaps from an earlicr bridge.

Cuts at Ringwood shown on Naish’s map are above the causeway carrying the A 31 across the valley. Starting above the site of Ashley Mill (NGR 135055), where only some brick walling remains, the navigation ran from the outfall under the present A 31 and West Street and along the Bickerley Mill stream past Moortown to rejoin the main river at NGR 145035. This diagonal route is very difficult to establish, especially since the 1969 roadworks in the area have virtually obliterated what was left. The whole area is reedy pasture and waterlogged and often flooded in winter, while gravel working took place in the Moortown area during the last century.

However, Kingsbury’s History of Ringwood (1894) quotes Entick’s British Empire of the eighteenth century in saying that ‘the Avon is made navigable to Salisbury but above Christchurch the navigation is affected by locks and sluices. At Ringwood the river forms an island, the navigation running on one side and a considerable stream on the other’. This would seem to suggest that the Bickerley Mill stream to Moortown shown by Naish was the navigation channel, since the main river is to the west. Kingsbury further adds that the navigation channel was still visible in the meadows in 1894, but no evidence could be proved at the present time.

Naish’s map shows three further short navigation cuts at Avon, Sopley and Winkton. The Avon stretch is now a shallow fordable stream close to the B 338 Christchurch road at.Avon Tyrell farm (NGR 144992); the Sopley stretch is the present millstream at Sopley Mill, the latter largely rebuilt in 1878. Little conclusive evidence of navigation works could be found at either site. At Winkton, however, is an open weir and fish pass at NGR 1 60956. This weir, recently reconstructed by the River Board, was an overflow weir of the millhead stream for Winkton Mill, demolished in the 1920s. Another weir lies across the line of the millhead and below are brick walls on both sides and a stone bed to the stream, which is dry in low-water periods. No trace of the mill remains, but the site can be reached by a footpath from the B 338 near Burton junction. There are suggestions that this site at Winkton was that of the first lock upstream of the navigation, but this cannot be proved.

In an attempt to improve the entrance into Christchurch Harbour over the bar, the ‘Clarendon Cut’ was begun in 1695 through the low sand hills of the Mudeford Sandspit on the east side of Hengistbury Head, and an ironstone breakwater was built on the south-east side of the cut. This scheme had been suggested by Yarranton, and the ‘pier’ is recorded on a map of 1698.* With the collapse of the navigation the Clarendon Cut silted up and the river resumed its major course through the ‘Run’ on its present line. John Smeaton, in a report on the harbour in May 1762, recommended the re-opening of the Clarendon Cut and the construction of a second breakwater to the south-west of the 1695 one, but his scheme was never carried out. Brindley surveyed the Avon for canal navigation in 1771,7 but nothing resulted. Despite various ninetcenth-century schemes to develop the harbour commercially, the idea of navigation inland was completely abandoned with the coming of the railways, and all that remains of the Clarendon Cut is a line of rocks offshore seen at low-tide at NGR 184912. However, one tangible piece of evidence remains from the seventeenth-century navigation efforts in the form of the quay at Christchurch itself which was rebuilt in the 1670s as part of the enterprise behind the 1664 Act (NGR 159924).

In the nineteenth century small coastal sculling craft and long skiffs for smuggling were built openly in inland fields (‘dockyard meads’) above Christchurch and brought downriver to the sea.® In 1907 the last public attempt to sail a small boat up the river under the right of navigation of the 1664 Act was made. Clearly such a use had been largely unchallenged until this time, when the owner of the fishing rights and riparian owner, Rev Mills of Winkton, sued the boatman for trespass. A ‘River Avon Public Rights’ Committee was set up in Christchurch with the support of the Mayor to raise money to challenge the denial legally, and in 1908 a QC gave h’s opinion that ‘the burden of proof of the continuing legality of the 1664 Act would be on the defence, and every effort should be made tv collect all the ancient evidence to strengthen that available. The case will be a difficult one... but there is a fair chance of the defence establishing the public right (of navigation) claimed’.

However, funds prevented the case being challenged, and judgement was given against those claiming navigation rights. The Act remains law, but no further efforts have been made directly to challenge the denial of navigation rights, chiefly through lack of evidence of proof of operation. Also it would involve a High Court case on whether the Act gave rights of navigation still over those parts which investigation has now established were part of the original navigation, or whether that right was only operative while the whole route was navigable throughout and so operated. Since many of the navigation sections no longer exist, this is clearly important.

Various authorities quote the river as having been navigable,’° but none quotes sufficiently legal evidence as proof. Recently, however, the author’s attention was drawn to documents" which prove conclusive.

The documents, made under oath and witnessed, were depositions of a lawsuit in 1737 by the Radnor Estate at Longford Castle over the use and construction of water-meadows in the area. Several citizens of Standlynch, where a mill was moved to assist construction, gave evidence:

Robert Tanner... Saith his father rented the mill at Standlynch and the fishery there for 60 years. That they used to go through the weir gap... with their boats when the hatches were up, and when they were down they used to haul their boats over the mead. Saith he has formerly for upwards of 40 ycars since seen barges go through the weir gap, but if the hatches were up no barges could now pass because there is now a wall in the middle of the gap....

Andrew Bourne... Saith he remembers two barges going through the weir when it was a lock.…

Tho. Hatcher... Saith he was at the building of the Navigation bridges about 35 years ago. Saith he remembers barges abuut 45 years ago coming from Salisbury to Christchurch and from Christchurch to Salisbury for several years together, that the navigators failing the Navigation ceased, and after some years was revived, and barges navigated as before. Saith no barge can go through the present weir gap because of the new wall in the middle. ...

Farmer Arnold... Saith the Navigation was begun about 45 years ago, and he remembers the barges navigating the river and coming through Standlynch where they were hauled through by windlass... .

There would appear, therefore, that there is no doubt the navigation was opened to traffic in the period 1684-95, that heavy flooding and/or financial problems caused a cessation around the turn of the century, but that, for a period of perhaps twenty years after, the navigation was again operable. From the archaeological evidence and documentary sources it would also be reasonable to presume that the early locks were turf-sided ‘flash’ locks and some of the bridges were of timber.

Following the flood disaster these were replaced by brick structures, the locks being possibly ‘pound’ locks, eg as at Britford. The land-owners clearly had every reason for ‘reclaiming’ their rights and land once the navigation proved uneconomic, and this, combined with the current vogue for water-meadows in this area which was gaining impetus, meant adaptation of the navigation works to serve an agricultural purpose, and within a comparatively short time. Even without the economic problems, the task of cutting and maintaining a firm and sufficiently deep channel through a lower valley of alluvium, sands and gravels, which was subject to flooding without extensive sidewall protection, banking and tributary control from the New Forest streams, was an impossible one at the time.

Further research is continuing both in the field and from documentary sources to answer several more questions. For instance, there is very little evidence of a towpath anywhere along the route and the boat shown in the Harbirdge painting of the nineteenth century is a sailing vessel. What was the motive power for the barges? And in what year was the Great Flood which washed away the works?